If you heard that an NFL player was six feet, two inches tall and weighed 210 pounds, you would not expect the player to be a lineman.

However, Bill Willis showed that a player of such small size (by professional football standards) could be a lineman, and in fact an outstanding lineman, in the NFL.

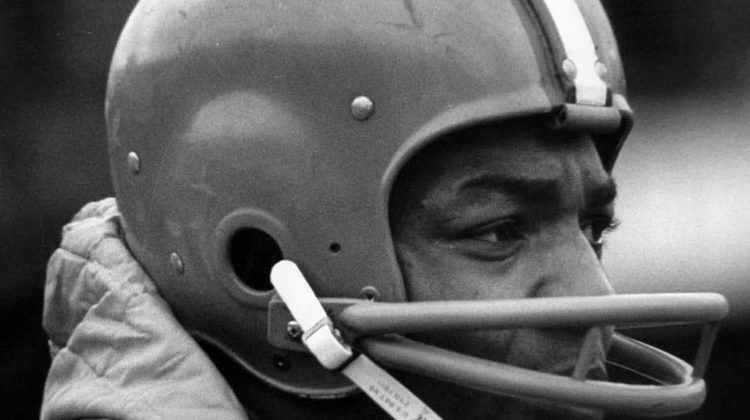

Nicknamed “The Cat” for his exceptional quickness, Willis was a star on the defensive line for the Cleveland Browns for eight seasons from 1946 to 1953.

Willis’ outstanding play earned him enshrinement in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

We take a look at the life of Bill Willis – before, during, and after his Cleveland Browns career.

The Early Years Through High School

William Karnet Willis was born on October 5, 1921 in Georgia.

Willis’ family moved to Columbus, Ohio in 1922.

Willis’ father, Clement, died of pneumonia on April 10, 1923.

Willis was raised by his mother, Williana (“Anna”), and grandfather.

It was not an easy childhood for Willis being raised as an African American without a father during the harsh economic conditions of the Great Depression in the 1930’s.

Columbus East High School

Willis attended Columbus East High School.

In high school, Willis participated in track and field and in football.

In track and field, Willis ran sprints and threw the shot put.

In football, Willis, based on his size, would have been expected to be a running back.

However, Willis’ older brother, Claude “Deacon” Willis, had been an “All-City” and “All-State” fullback at Columbus East High School six years earlier.

Because Willis did not want to be constantly compared to his older brother as a running back, Willis wanted to play a different position.

Willis and his coach at Columbus East High School, Ralph Webster, agreed that Willis could play end.

Willis started at end as a sophomore in 1938.

Willis ultimately played both end and tackle in high school.

By 1939, Willis had become a star.

Remembering playing against Willis that year, future Ohio State and Cleveland Browns teammate Gene Fekete said:

“The only recollection I have of that game is that we had a fifth man in our backfield, and it was him”.

In 1940, Willis earned “All-City” and “Honorable Mention All-State” honors at Columbus East High School as a senior.

Today, a player of Willis’ ability would be recruited out of high school by schools across the country.

However, African-American players faced expansive racial discrimination in 1940.

Willis’ brother, Claude, was rejected by major schools when he graduated from high school and ended up attending Claflin University, a historically black college.

Not receiving any major school recruiting offers after high school, Willis actually worked for a year.

His high school coach Ralph Webster encouraged Willis to attend University of Illinois (where Coach Webster had attended).

However, before Willis committed to University of Illinois, the new coach at Ohio State University, Paul Brown, recruited Willis.

Willis decided to attend Ohio State University, and he enrolled there in 1941.

College Years

Willis joined the Ohio State football team as a sophomore in 1942.

And let’s remember the great Bill Willis from The Ohio State University! Another color barrier breaker. Willis was a National Champ and All-American at OSU and a perennial All-Pro and Champ with the AAFL and NFL’s Browns. He is in both the College and Pro Football Halls of Fame! pic.twitter.com/jYs99gtWNr

— Doyle Rausch 🤘 (@DoyleRausch) February 14, 2018

He played both on offense as a tackle and on defense as a middle guard (a defensive line position opposite the center).

In 1942, the Buckeyes had a 9-1 record and finished the season ranked first in the nation in the final Associated Press poll.

The 1942 team is regarded as the first football national championship team for Ohio State.

Willis helped the Buckeyes in 1942 outscore their opponents 337-114 (including posting two shutouts and four times holding the opposing offense to less than 10 points).

According to Willis’ College Football Hall of Fame biography:

“A splendid leg-sprint to the hit, a bursting quickness through the block and a pulsating power in clearing the path for the runner – Bill Willis was all of this as a tackle on the Ohio State national championship team of 1942”.

In 1943, Willis was voted to the first team “All-Big Nine Conference” (the predecessor to the Big 10) football team at tackle by both the Associated Press and United Press.

Ohio State stumbled to a 3-6 record in 1943, hampered by the loss of many players due to World War II.

Willis had volunteered for the U.S. Army, but was classified as “4-F” (generally exempting him from service) because of varicose veins.

In 1944 (with Carroll Widdoes replacing Paul Brown as head coach), Ohio State rebounded with a 9-0 record, finishing the season ranked second in the nation (to Army) in the final Associated Press poll.

Willis was a key contributor, as the Buckeyes outscored their opponents 287-79 (including two shutouts and five times holding the opposing offense to less than 10 points),

In 1944, Willis again was voted to the first team “All-Big Nine Conference” football team at tackle by both the Associated Press and United Press.

In addition, on a national level, in 1944, Willis was voted “All-American” (the first African-American “All-American” at Ohio State) at tackle by “Look” magazine, the Sporting News, the United Press (first team), the Associated Press (second team), the Football Writers Association of America (second team), and the International News Service (second team).

Willis helped Ohio State quarterback Les Horvath win the Heisman Trophy in 1944 with his outstanding blocking.

Again, quoting from Willis’ College Football Hall of Fame biography:

“A sprinter’s speed made Willis one of the greatest linemen at running interference, and many an opponent left Ohio Stadium feeling the pains of a Willis pop-block. . . . Buckeye fans who enjoyed those championship years remember vividly the sight of Heisman Trophy winner Horvath slipping off the shoulders of the straining Willis and running to glory”.

On defense, Willis was as strong, if not even stronger, of a player.

Jack Park, the author of “The Official Ohio State Football Encyclopedia”, stated:

“His [Willis’] real claim to fame was that he was just so quick off the ball. He was just through, and into the backfield to break up a play. . . . The Outland [Trophy] and the Lombardi Award weren’t around when Bill was playing at Ohio State. Had they been, I think it’s pretty safe to say that Bill Willis would probably have won those, and if not been very high in the voting for those awards”.

In addition to playing football, as further evidence of his speed, Willis was a sprinter on the track team at Ohio State, running in the 60-yard and 100-yard events (including at the Penn Relays).

Academically at Ohio State, Willis maintained a high-class ranking in Business Administration.

Willis graduated from Ohio State in 1944.

The Pro Football Years

After Ohio State, Willis played in both the 1944 College All-Star Game and the 1945 College All-Star Game, which potentially could have been Willis’ last games.

Just as broad racial discrimination at first adversely affected Willis’ transition from high school to college, it also at first threatened Willis from having any professional career.

In 1945, no African Americans played in the NFL.

Apparently, without the ability to play pro football, Willis took a job as the head football coach and athletic director at Kentucky State College, a historically black college.

In evaluating Willis’ career, it is important to remember that he did not play football during two of his potentially prime playing years (the year after high school and the year after college).

While Willis was successful in his year at Kentucky State College (losing only two of 10 games), Willis still wanted to play pro football.

1946-1949

Willis reached out to his former coach at Ohio State, Paul Brown, who was starting the Cleveland Browns franchise in the new All-America Football Conference (“AAFC”).

When Brown did not respond to Willis, Willis considered accepting an offer from the Montreal Alouettes to play in the Canadian Football League.

Brown in fact did want Willis to join the Browns.

However, for “public relations” purposes, Brown did not want to appear to the rest of the AAFC that he was having direct contact with an African American to join the team; such was the unfortunate state of the world in 1946.

Instead, Brown had a newspaper columnist contact Willis and advise him to attend the Cleveland Brows training camp in Bowling Green, Ohio as a “walk-on” for a tryout.

It may not have been by direct contact, but once again, just as he had recruited Willis to Ohio State, Paul Brown played a critical role in advancing Willis’ football career.

Willis made an immediate positive impression at training camp.

On a series of plays against different Browns centers, including future Pro Football Hall of Famer Frank Gatski, Willis knocked over the centers and also tackled Browns quarterback Otto Graham.

One of the centers, Mike Scarry, recalled:

“Everybody got knocked down. We used to just line up over the ball and snap it. With Willis, though, you had to put the ball as far as you could out in front of you, to get as far away from him as you could. He changed the whole way we snapped the ball”.

Scarry (as did many offensive linemen who played against Willis), thinking that no player could be so quick across the line, insisted that Willis must be offsides, but such was not the case.

“What I had been doing was concentrating on the ball. The split second the ball moved, or the center’s hands tightened, I charged”.

Brown was so impressed he signed Willis to the Browns roster that day (at an annual salary of $4,000).

Willis thereby became the first African-American player signed in the AAFC.

The Los Angeles Rams in the NFL had signed two African Americans, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, just before Willis signed.

With Kenny Washington, reintegrated the NFL. (Bill Willis and Marion Motley integrated the AAFC with the Cleveland Browns.) Shown during UCLA years below at left, with Washington and, at center, Jackie Robinson. pic.twitter.com/quSv7Ahi4l

— John Thorn (@thorn_john) July 26, 2020

However, as Washington and Strode played sparingly for the Rams, Willis and African-American Browns teammate Marion Motley (signed a week after Willis) actually played in a regular season game before Washington and Strode, and Willis and Motley had more successful “Hall of Fame” careers, Willis and Motley are seen as greater racial trailblazers for the growth of African-American participation in professional football after World War II.

Checking in at #4 on our Historic Artifacts list are Marion Motley’s & Bill Willis’ 1946 rookie player contracts. Their success on the field paved the way for African Americans to have better opportunities in professional football & beyond.

More: https://t.co/N2TPQ5gyxQ@Browns pic.twitter.com/2llYEC521r

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) April 3, 2020

Motley was Willis’ roommate with the Browns.

Willis again initially played both offense and defense with the Browns.

Eventually, changes in substitution rules enabled Willis to focus on the defensive middle guard position.

In 1946, Willis helped the Browns compile a 12-2 regular-season record, outscoring their opponents 423-137 (and posting four shutouts and holding opposing offenses to less than 10 points in eight regular-season games).

September 6, 1946. Cleveland Municipal Stadium. 60,000 plus to see Bill Willis and Marion Motley. Go Browns. pic.twitter.com/xTiEFOKDMO

— Vic Whitney (@whitney_vic) August 22, 2019

Willis and Motley missed a December 3, 1946 game in Miami against the Miami Seahawks.

They were left in Cleveland because of death threats against them if they played.

Willis faced racial taunts throughout his career from opposing players and fans.

“You could hear a lot of, ‘Get that black son of a bitch’”.

However, Willis generally responded with restraint and let his excellent play on the field do the talking.

A little-known fact is that this restraint by Willis (and Marion Motley) in 1946 in a contact sport was one factor that helped convince Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey that Jackie Robinson could break baseball’s “color barrier” in 1947 (in a generally non-contact sport).

The Browns defeated the New York Yankees 14-9 on December 22, 1946 to win the first AAFC championship.

In 1946, Willis was voted “1st Team All-NFL/AAFC” by the “Chicago Herald American”, and “1st Team All-AAFC” by the AAFC (at right guard).

The Browns repeated as AAFC champion in 1947.

Cleveland had a 12-1-1 record in the regular season (outscoring opponents 410-185, with two shutouts, and holding offenses to less than 10 points in five regular season games) before defeating the New York Yankees in the 1947 AAFC championship game 14-3 on December 14, 1947.

In 1947, Willis was again voted “1st Team All-AAFC” by the AAFC (at right guard).

The Browns won their third consecutive AAFC championship in 1948, with an undefeated 15-0 season, including a 49-7 rout of the Buffalo Bills on December 19, 1948 in the AAFC championship game.

Cleveland outscored their opponents 389-190, with the Browns defense holding opposing offenses to less than 10 points in four games, in the regular season.

Willis was voted in 1948 “1st Team All-AAFC” by the AAFC for the third consecutive year.

BILL WILLIS

With the Rams leaving Cleveland for L.A., the @Browns formed as a charter member of the AAFC.

Coach Paul Brown, an @OhioStateFB legend who said he never made a roster choice based on color, signed former Buckeye Bill Willis.

Willis became a Hall of Famer. pic.twitter.com/tqnzKxrKZO

— NFL Throwback (@nflthrowback) February 9, 2019

In addition, in 1948, Willis was voted “1st Team All-AAFC” by United Press International and the New York Daily News, “2nd Team All-NFL/AAFC” by the Sporting News, and “2nd Team All-AAFC” by the Associated Press.

In 1949, the Browns won their fourth consecutive AAFC championship, with a 9-1-2 record in the regular season, outscoring opponents 339-171 (including posting two shutouts and holding opposing offenses to less than 10 points in seven games).

The Browns then defeated the Buffalo Bills 31-21 on December 4, 1949 in the divisional round of the playoffs before winning the AAFC championship game 21-7 against the San Francisco 49ers on December 11, 1949.

Willis had his only professional football interception in 1949, which he returned for six yards.

Willis was voted in 1949 “2nd Team All-AAFC” by the AAFC, United Press International, and the New York Daily News.

1950-1953

The AAFC disbanded after the 1949 season, and the Browns moved from the AAFC to the NFL.

However, this change in leagues did not affect the excellence of Cleveland or Willis.

In 1950, the Browns finished the regular season with a 10-2 record, outscoring opponents 310-144.

The Browns defense posted a shutout and held five opposing offenses to less than 10 points in the regular season.

The two regular-season losses of the Browns were to the New York Giants, who Cleveland met again on December 17, 1950 in the divisional round of the playoffs.

The Browns avenged their two regular-season losses to the Giants, by beating New York 8-3.

Willis made probably the most-remembered individual play of his NFL career in the game when he tackled Giants running back Gene “Choo-Choo” Roberts from behind on a long reception in the fourth quarter to prevent a touchdown and preserve the victory for Cleveland.

Willis also scored his only NFL points in the game, tackling Giants quarterback Charlie Conerly in the end zone for a safety.

The following week, on December 24, 1950, Cleveland defeated the Los Angeles Rams 30-28 to claim their first NFL championship.

In 1950, Willis was invited to his first NFL Pro Bowl and voted “1st Team All-Pro” by United Press International and the New York Daily News (at middle guard).

In 1951, Cleveland again advanced to the NFL championship game with an 11-1 regular-season record before losing to the Los Angeles Rams 24-17 on December 23, 1951.

The Browns outscored opponents 331-152 during the regular season (including posting four shutouts and holding opposing offenses to less than 10 points in five games).

Willis recovered a fumble in 1951.

He also was invited to his second consecutive NFL Pro Bowl, and voted “1st Team All-Pro” by the Associated Press, United Press International, and the New York Daily News, in 1951 (at middle guard).

Offensive starters in the 1st modern #ProBowl in Jan. 1951. Note the average weights at the bottom. (This was Pre-Iron Pumping.) 7 HOFers here — Tom Fears, Lou Creekmur, Bob Waterfield, Lou Groza, Bill Willis, Otto Graham & Marion Motley (4 #Browns, 2 #Rams & a Lion). #NFL pic.twitter.com/LclitWg7wc

— Dan Daly (@dandalyonsports) January 25, 2019

The Browns had a similar season result in 1952 as in 1951, advancing to the NFL championship game on December 28, 1952, but losing to the Detroit Lions 17-7.

Cleveland had an 8-4 regular-season record in 1952, outscoring opponents 310-213 (posting one shutout and holding three opposing offenses under 10 points in regular-season games)

In 1952, Willis was invited to his third consecutive NFL Pro Bowl and voted “1st Team All-Pro” by the Associated Press and the New York Daily News and “2nd Team All-Pro” by United Press International (at middle guard).

Cleveland in 1953 had an 11-1 regular-season record, outscoring opponents 348-162 (including posting two shutouts and, in four games, holding opposing offenses under 10 points).

However, for the third straight year, the Browns lost in the NFL championship game – 17-16 to the Detroit Lions on December 27, 1953.

Willis recovered another fumble in 1953. In addition, he was voted “1st Team All-Pro” by the Associated Press and “2nd Team All-Pro” by United Press International (at middle guard).

After the 1953 season, at the age of 32, Willis retired from the NFL.

Willis’ professional football accomplishments were impressive.

Over eight seasons, Willis played in eight league championship games, won five league championships, was invited to three NFL Pro Bowls, and was voted to numerous “All-Pro” teams.

The Years After The NFL

Willis married Odessa Porter in 1947 (they were married until her death in 2002).

They had three sons, William, Jr., Clement, and Dan.

Willis is a good example of an NFL player who retired because he wanted to focus on non-football activities that could benefit society.

Willis was principally interested in working with and helping young people, especially troubled youth.

After his retirement, Willis became assistant commissioner of recreation in Cleveland’s recreation department (at an annual salary of $6,570).

In 1963, Willis returned to Columbus (living not far from where he had grown up) and worked for two decades at the Ohio Department of Youth Services (also known as the Ohio Youth Commission and the Ohio Youth Council), a state agency created to combat criminal behavior among young people.

Willis ultimately retired as director of the Ohio Department of Youth Services in 1983.

In 2006, Ohio state legislator Ralph Regula recognized Willis’ work in working with troubled youth, stating:

“Many of you know him as an outstanding player at Ohio State. Many of you know him as an outstanding player with the Cleveland Browns. But thousands of men got a second chance because of him as the chairman of the Ohio Youth Council. He rebuilt the lives of many young people”.

Willis died in Columbus of complications from a stroke on November 27, 2007, at the age of 86.

Two Enduring Legacies

Willis is a unique football player in that he has two enduring legacies.

Willis is remembered both for his playing ability and for being a trailblazer for future African-American players.

As a football player, it is difficult to measure Willis’ performance because official sack or tackle statistics were not kept when Willis played.

Instead, we can look to the honors Willis received and the comments made about Willis by those who saw him play.

In 1969, Willis was selected to the NFL’s “1940s All-Decade Team” (at guard).

As noted above, Willis was inducted in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1971.

In 1977, Willis was inducted in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Bill Willis helped the @Browns win 5 league titles during his 8-year career #BlackHistoryMonth pic.twitter.com/qrXaUgzFQh

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) February 17, 2017

He was presented by Paul Brown.

Willis’ Pro Football Hall of Fame biography states, as a quotation from Willis:

“The split second the ball moved, I charged and I always came at a different angle . . . I could unleash a pretty good forarm block and a rather devastating tackle too”.

HOFer Bill Willis was born OTD in 1921. Played 8 seasons for @Browns. Selected to 3 Pro Bowls & @NFL 1940s All-Decade Team. pic.twitter.com/UtKwGI4kBL

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) October 5, 2017

In addition, in 1977, Willis was one of 23 charter members of the Ohio State Varsity O Hall of Fame; to be eligible, a Buckeye athlete must have earned at least one varsity “O” letter.

Willis was inducted for both football and track and field.

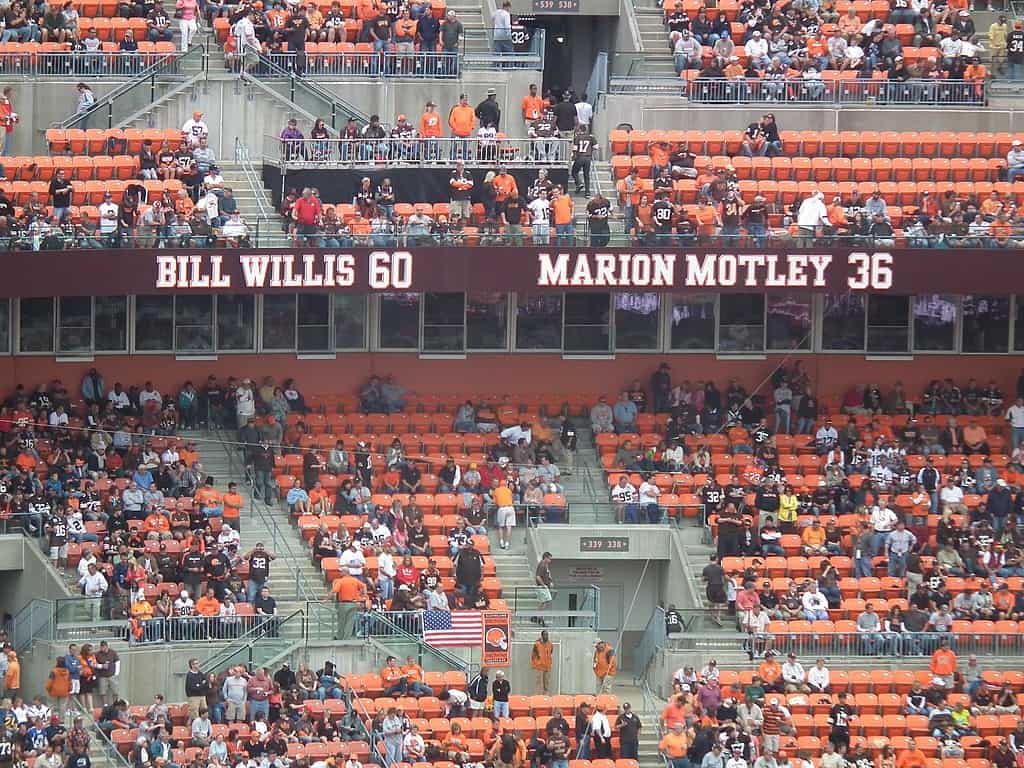

In 2001, Willis was one of 13 charter members of the “Cleveland Browns Legends” program.

In 2007, Willis’ jersey number “99” was retired by Ohio State University (the first Buckeye lineman and defensive player to have his jersey number retired).

In 2010, Willis was part of the inaugural class of 16 Cleveland Browns having their names displayed in the Browns’ “Ring of Honor” (around the upper deck of Cleveland’s FirstEnergy Stadium).

These honors are consistent with the comments made about Willis’ play.

According to Paul Brown, Willis literally changed how defense was played.

“He often played as a middle or nose guard on our five-man defensive line, but we began dropping him off the line of scrimmage a yard or two because his great speed and pursuit carried him to the point of attack before anyone could block him. This technique and theory was the beginning of the modern 4-3 defense, and Bill was the forerunner of the modern middle linebacker”.

Fellow Pro Football Hall of Famer Clyde “Bulldog” Turner said about Willis:

“The first guy that ever convinced me that I couldn’t handle anybody I ever met was Bill Willis. He didn’t look like he should be playing middle guard, but he would jump right over you”.

Sports Illustrated pro football writer Paul Zimmerman stated:

“The press book had a memo to photographers that Willis must be shot at 1/600th of a second to capture his speed. . . . Willis . . . was, you see, the fastest interior lineman who ever played the game”.

As a football trailblazer, Willis is revered by many future African-American football players.

Heisman Trophy winner Archie Griffin “was pretty much in awe” when he met Willis. Griffin stated:

“I’m sure it wasn’t easy for Bill. I’m sure there were times where they wouldn’t have let him play, certainly as you go south, they weren’t going to let him play. I’m sure that was a very difficult situation for him. . . . When that type of thing happens, it opens doors. I think it really paved the way for African-Americans to participate in sports the way that they do today”.

“All-Pro” tackle Willie Anderson said of Willis:

“Young guys should know about him. Guys like him gave me a start. He paid a price. It humbled me to learn some of the things he went through”.

When you leave two enduring legacies, it is not surprising that your name is used, even after your death.

The Bill Willis Trophy is presented annually by the Touchdown Club of Columbus to the nation’s top collegiate defensive lineman.

The Bill Willis Trophy was awarded to Myles Garrett in 2015.

On July 14, 2020, the Browns announced that Ashton Grant would be the first-ever recipient of the Bill Willis Coaching Fellowship.

“The opportunity is huge. I’m just thinking about how I can be of service to all the coaches and players I’ll be working with.”

Meet Ashton Grant, our first recipient of the Bill Willis Coaching Fellowship » https://t.co/rQAP2JvWqw pic.twitter.com/pAGGx1m5HC

— Cleveland Browns (@Browns) July 14, 2020

The Bill Willis Coaching Fellowship is intended to provide opportunities and experience to minority coaches; Grant (a quality control coach at College of the Holy Cross) will spend a full season with Cleveland’s coaching staff and assist coaches with week-to-week game plans and talent evaluations.

It seems only appropriate that Bill Willis, whose life is already associated with outstanding defensive play, African-American representation and advancement, and helping others, posthumously will continue to be associated with these concepts and values through the Bill Willis Trophy and the Bill Willis Coaching Fellowship.

The legacy of Bill Willis will only grow in the future.

NEXT: What Went Wrong For Bill Belichick In Cleveland (Complete Story)