On that momentous day of April 15, 1947, Robinson initiated a turning tide in baseball.

Up until that day, if African-Americans wanted to play professional baseball, they could only participate in the Negro League.

Once the Brooklyn Dodgers decided to push back on racial segregation by signing Robinson, the resistance met initially was abated slowly but surely over the next few decades.

Larry Doby would also become the first African American player in the American League to break major league baseball’s “color barrier.”

While Robinson’s monumental feat is heralded far and wide, a less heralded moment has not always received the attention it deserves.

One year before Robinson took the diamond for the Dodgers, pro football’s color barrier was breached.

In early 1946, the Los Angeles Rams signed Kenny Washington and Woody Strode.

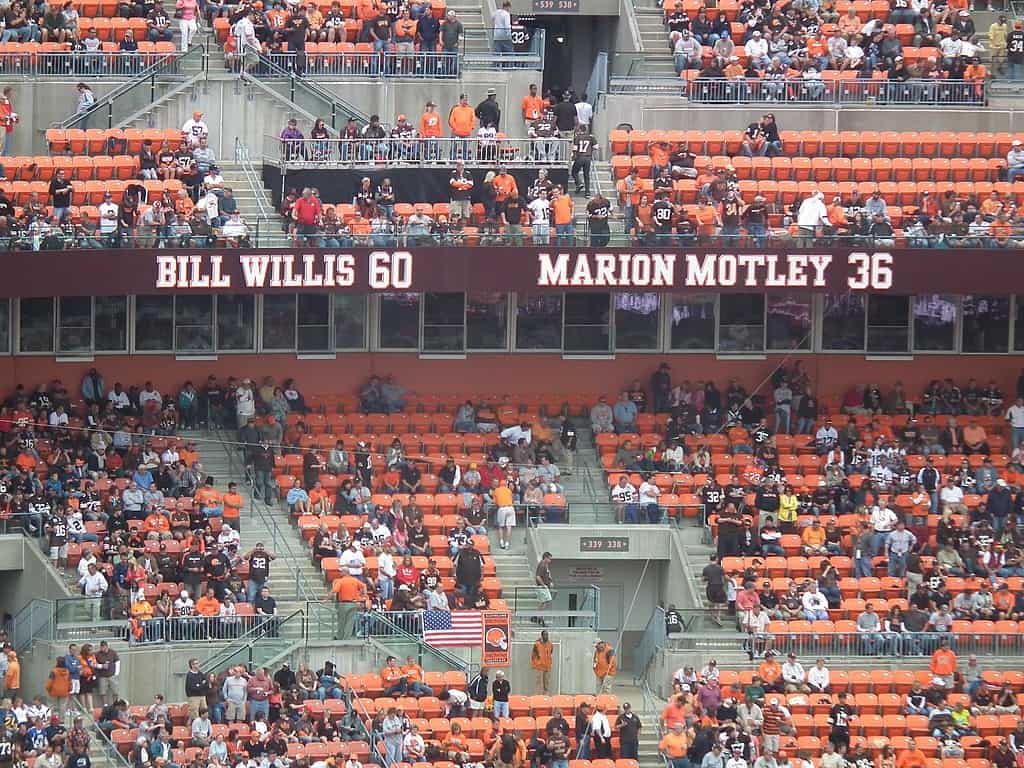

A few months later, Cleveland Browns head coach Paul Brown signed Bill Willis and Marion Motley.

All four became the first African-American men to play professional football in the modern era.

Before there was Colin Kaepernick, there was Marion Motley. https://t.co/7Wex55OUNC

— Chris Murray (@ByChrisMurray) June 8, 2020

Willis and Motley quickly achieved success as members of Brown’s new team.

However, it is Motley who has stood the test of time as one of the quintessential running backs for the franchise.

Motley’s size and speed have led many NFL historians to boast that he could have not only played in the modern day game but thrived.

Years before the mighty Jim Brown took the field for Cleveland, “The Train” intimidated and bulldozed his way through defenders and into the collective conscience of football fans.

Here is a look back at the life and career of Marion Motley.

Outsized at the Start

Marion Motley was born on June 5, 1920 in Leesburg, Georgia.

Given the severe racial tensions in the south at the time, Motley’s family were part of the “Great Migration” of African-American families that looked for work in the northern part of the country.

The Motley family eventually settled in Canton, Ohio when Marion was only two.

Canton turned out to be a serendipitous landing spot for Motley.

As Motley got older, he took up athletics, especially football, which was the area’s passion.

In junior high school, Motley’s build morphed to the point where a junior high football manager wouldn’t give him pads.

When he was finally permitted to practice, his teammates insisted that Motley wear pads.

This was requested not so much for Motley’s protection, but for the protection of the players he practiced against.

While attending Canton McKinley High School, Motley played football and basketball.

His powerful frame and athleticism burned brightest on the gridiron, however.

By the time he was a sophomore, Motley had already bloomed to 6-1, 200 pounds.

He became a starter for the Bulldogs, but was put at the guard position.

During that 1936 season, the Bulldogs rolled through the regular season until they played Massillon in the season finale.

Canton McKinley lost to Massillon 31-0.

Proof that football back then truly was a small world, Massillon’s coach was a man named Paul Brown.

Just a reminder on Marion Motley’s 100th birthday today, Timeless Rivals is available to watch on Amazon Prime https://t.co/Yw8JBwW3L1 pic.twitter.com/WBLCCmLqPZ

— 🐾The 1 Bulldog (@CantonMcKinley) June 5, 2020

As a junior, Motley was moved to fullback and was having a monster year.

That season, Motley ran for 950 yards on 58 carries.

That translates to 16.3 yards per carry (yes, you are reading that correctly).

He also tacked on 10 rushing touchdowns and tried his hand at throwing the ball, completing six of nine passes for 229 yards and four scores.

Inexplicably, Canton McKinley’s coach put Motley back at guard for the re-match against Massillon and Brown so that a previously injured back could play.

Not surprisingly, Massillon prevailed again 19-6, the Bulldogs only loss of the season.

To prove that his 1937 stats were no anomaly, as a senior in 1938 Motley ran for 1,228 yards on 69 carries (17.8 ypc average) and threw for 454 yards and seven touchdowns.

The Bulldogs had another undefeated year, until they faced rival Massillon.

For the third time in three years, Paul Brown’s squad upended Motley and the Bulldogs 12-0.

During his three years as a starter for Canton McKinley, Motley’s teams went 25-3 with all three losses coming at the hands of Brown and Massillon.

During his high school career, Motley racked up solid numbers, to say the least.

His time at Canton McKinley ended with 2,178 rushing yards at a 17.2 yards per carry clip and 683 yards passing and 11 touchdowns.

All told, he scored 174 points in high school.

When the post-season awards came around, Motley was named Third-team All-Ohio for 1938.

To this day, many football historians, as well as Canton locals, believe Motley’s race was a factor in the decision not to give him First-team All State honors.

Race also appeared to be a factor in why there were scant numbers of college recruiters interested in Motley.

Despite his obvious talent, Motley didn’t have much choice and decided to head south to play college football.

The Jim Crow South Leads to Motley’s Move West

With not very many college playing opportunities, Motley went south to South Carolina State.

The college, a historically black institution of higher learning, was not immune to the rampant racism in the Jim Crow south.

Motley had no desire to live in that negative environment.

So, he packed up and went back to Canton.

The following year, transferred as far away as possible from the hatred he had witnessed in South Carolina.

Former Canton McKinley coach Jimmy Aiken was now coaching the University of Nevada Wolf Pack in Reno.

Motley took advantage of the connection and traveled west.

Today is a special day in Wolf Pack history as it would have been the 100th birthday of Marion Motley, a trailblazer who is a member of both the NFL and Nevada Athletics Hall of Fame.

Read more: https://t.co/0GOxZPabIb#BattleBorn // #NevadaGrit pic.twitter.com/dW9U966PwB— Nevada Football (@NevadaFootball) June 5, 2020

While Motley played well for the Wolf Pack, he found that deep-seeded racism was in every corner of the country.

While the University of Nevada football team may have been a relative safe haven for minority athletes, the opponents the school faced were not as kind to Motley and other Wolf Pack athletes of color.

In a message Motley gave to the university’s Oral History Program years later, Motley explained what he and others faced against some opponents.

“They called us names and everything, and I just wouldn’t even talk to them. If I caught one in my way, I ran over him. I ran smack over him … we got a lot of respect that way.”

Before a game against the University of Idaho, the Vandals head coach told Aiken that he did not want Motley to play against them.

Aiken, who was kind and cordial off the field could be a firebrand on the field, especially during games.

When the Idaho coach told Aiken he did not want Motley to play in the game, Aiken went ballistic, according to Motley.

“When (the Idaho coach) told Jim I couldn’t play, I had to grab Jim and pick him up around his waist and hold him off the ground … He was going to punch this guy in the mouth,” Motley said.

Needless to say, the message was received loud and clear and Motley played in the Idaho game.

During his time in Reno, Motley had flashes of brilliance, but he also sustained numerous injuries.

After suffering a particularly bad knee injury in 1943, he left the University of Nevada and went home to Canton.

In his mind, he was going home to find work and his football life was over. However, he was not expecting to connect with an old foe that would change the course of his life.

Motley Returns to Football under Brown

As Motley was returning to Canton, America at the time was immersed in World War II.

On Christmas Day of 1944, Motley decided to do his part to serve his country and enlisted in the Navy.

After enlisting, he was sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago.

Not long after arriving, Motley decided to play for the base’s football team.

It just so happened that the team was coached by Paul Brown, Canton McKinley’s old Massillon nemesis.

Brown had been the head coach at Ohio State University but was at the base serving in the Navy on extended leave.

Brown’s team proved to be a juggernaut and played college football powerhouses such as Ohio State and Notre Dame.

Motley played both fullback and linebacker and he was integral in the team’s success.

In one of the biggest upsets in football history, Great Lakes defeated Notre Dame handily in 1945 by a score of 39-7.

Football historians remember the game not only because of the upset, but also because of a new play design by Brown.

The design was rather simple, but revolutionary.

Quite simply, it was a delayed handoff.

The offense would set up to pass, therefore pulling the defensive line into a full rush and the defensive backs to drop back in coverage.

At the last second, instead of passing, the quarterback hands off to the running back.

This play would later be termed a “draw.”

#bengals Paul Brown #whodey #newdey 1st coach to use game film to scout opponents, hire a full-time staff, test players on knowledge of a playbook. invented modern face mask, practice squad and the draw play. played role in breaking professional football’s color barrier – LEGEND pic.twitter.com/EsQs6J981o

— Bengal Jim’s BTR (@bengaljims_BTR) June 1, 2019

The play worked to perfection and soon after became a regular staple in football play books throughout the country.

With the war over, Motley returned to Canton in 1946 and found work in a steel mill.

He had planned to return to Reno at some point to finish his degree.

However, just down the road in Cleveland, Paul Brown had started a new team called the Browns in the All-American Football Conference (AAFC).

Motley believed he might be able to make some money as a pro football player and wrote Brown a letter asking for a try-out.

Surprisingly, Brown declined telling Motley that he had all the fullbacks he needed.

Only weeks later, Brown changed his mind and reached out to Motley, forever changing Motley’s life as well as the course of pro football history.

Not coincidentally, @browns coach Paul Brown had signed another FB the day before — one Marion Motley, a former star at @NevadaFootball, who had played for a Navy team that Brown had coached during World War II. (6/8) pic.twitter.com/GNNaiVCEdB

— Mark Beech (@MarkBeech2pt0) August 13, 2019

Motley and Willis Break Barriers

As Cleveland prepared for their training camp in 1946, Brown contacted one of his former players at Ohio State, Bill Willis.

Willis had been an All-Conference selection in the Big Ten under Brown and was known to be a quick and agile defensive lineman.

Brown invited Willis to try out for the team.

He then contacted Motley to ask if he would be willing to come for a try out as well.

Motley later revealed that he thought Brown’s motive for the invite had nothing to do with his playing ability.

“I think they felt [Willis] needed a roommate,” Motley later said. “I don’t think they felt I’d make the team. I’m glad I was able to fool them.”

Both Motley and Willis’ talent was too good to pass up and they made the Cleveland roster coming out of training camp.

Motley signed his first contract for over $4,000 a year.

However, just making it to the active roster of a professional football team was a monumental feat then.

In 1946, it had been over a quarter century since an African-American, Fritz Pollard, had played pro football.

At the other end of the country, the LA Rams of the National Football League also signed two African-Americans, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode.

Motley, Willis, Washington, and Strode had effectively broken the color barrier in professional football for good.

Happy 100th birthday to the great Marion Motley! He, along with Kenny Washington, Woody Strode & Bill Willis, broke pro football’s color barrier, 1 year before the great Jackie Robinson played for the Dodgers.

Motley was also the 2nd black player voted into the Pro Football HOF. pic.twitter.com/x0kFW9oV7M

— Four Verts 🏈 (@FourVerticals_) June 5, 2020

Motley and the Browns Establish a Winning Tradition

In their relatively short existence, Brown had assembled a talented core including quarterback Otto Graham, kicker and tackle Lou “The Toe” Groza, and receivers Mac Speedie and Dante Lavelli.

Motley only added to the team’s embarrassment of riches, playing both fullback and, occasionally, linebacker.

In his rookie year of 1946, Motley gained 601 yards on 73 attempts for a 8.2 average and five touchdowns.

His stats led him to a fourth overall ranking in the AAFC that year.

The Browns went 12-2 and defeated the New York Yankees (football team) 14-9 for the title.

During the game, Motley gained 98 yards and a touchdown.

For the next three years, it was more of the same for Motley and the Browns.

Motley ran for 889 yards and eight scores in 1947 and Cleveland beat the Yankees again (with Motley adding 109 yards) 14-3 for the championship.

In 1948, Motley ran for a career best 964 yards and five TDs and the undefeated Browns beat the Buffalo Bills 49-7 for the title.

During the game, Motley ran over and through Bills players for 133 yards and three TDs.

Motley’s yardage dipped considerably in 1949, gaining only 570 along with eight touchdowns.

The Browns took down the San Francisco 49ers 21-7 for the championship with Motley contributing 75 yards and a score.

#Browns History 🏆

Cleveland won all four AAFC championships and amassed a 52-4-3 winning record. When the AAFC folded after the 1949 season, many insisted a major reason was the Browns’ dominance that eliminated any viable competition. pic.twitter.com/JauT6vJEvB

— BROWNS OR DIE 💀 (@BrownsorDie) December 10, 2019

In 1950, the Browns moved to the National Football League and didn’t waste time dominating the competition in their new league.

During the Browns inaugural NFL season, Motley had his third highest career rushing total with 810 yards and added three scores.

His yardage that season was enough to crown him the NFL’s rushing champion, the first African-American in league history to do so.

Cleveland had a 10-2 regular season and won their first NFL championship 30-28 against the LA Rams.

More on Marion Motley, born 100 years ago today:

• Second African American inducted into the PFHOF (1968)

• NFL’s first black rushing champion (810 yards in 1950)

• AAFC All-Time Leading Rusherhttps://t.co/D8s622GGYn— Kevin Gallagher (@KevG163) June 5, 2020

The Beginning of the End

During the 1951 season, Motley sustained a bad knee injury that continued to linger for the next few seasons.

That year, he gained only 273 yards and the Browns lost their first championship game 24-17 against LA.

In 1952, Motley rebounded, slightly, with 444 yards rushing while the team lost again in the title game, this time to the Detroit Lions 17-7.

1953 proved to be Motley’s final season in a Browns uniform.

With his knee still bothering him, Motley barely contributed on the field and had the lowest rushing total during his time in Cleveland with 161 yards.

In 1954, Motley attempted to return to the Browns for another season, but thought better of it due to his injuries and age and quit the team before the season began.

It turned out to be a wise decision as Brown most likely would have cut Motley.

“Marion realized that his knee was weak and did not feel that it was coming around,” Brown said at the time. “He was one of the truly fine fullbacks in his prime, the type that comes along once in a lifetime. I certainly never will forget some of his runs and I imagine Cleveland football fans feel the same.”

One Last Gasp in Pittsburgh

Motley took the rest of the 1954 season off to rest and recuperate.

Then, in 1955 he headed to Pittsburgh after the Browns (who still held his rights) traded him to the Steelers.

During his final season as a pro, Motley ran for only eight yards and mainly played linebacker.

Clearly seeing his decline, Pittsburgh cut Motley from the team before the season ended.

Motley’s Retirement and Influence on the Game of Football

If one were to add Motley’s career totals in the NFL with his numbers in the AAFC, he retired with 4,720 yards rushing (5.7 ypc) and 31 touchdowns.

His rushing total would put him at number six all time on the Browns rushing list if his AAFC yards were counted.

After retiring in late 1955, Motley attempted to stay close to the game.

He turned to Brown for a coaching position on his staff.

Curiously, Brown declined and told Motley he should find work in a steel mill instead.

Motley continued to be turned down for coaching opportunities and eventually found work as a whisky salesman.

In 1964, Motley again sought work as a coach on the Cleveland staff.

He was told once again that all positions had been filled.

However, not long after, the Browns hired a coach named Bob Nussbaumer as an assistant.

Understandably upset, Motley wrote a statement to the media saying,

“When I heard of the hiring of a new assistant, I began to wonder if the full reason is whether or not the time is ripe to hire a Negro coach in Cleveland on the professional level.”

Art Modell, Cleveland’s owner at the time, dismissed Motley’s claim.

In the late 1960s, Graham was coach of the Washington Redskins and Motley sought out his old teammate for a coaching spot.

This time Motley was turned away by his former quarterback.

Eventually, Motley became a coach with the Cleveland Dare Devils in 1967.

The Dare Devils were an all girls professional football team that ended up folding after a few exhibition games.

In 1968, Motley was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his home town of Canton.

At the time, he was only the second African-American player inducted.

Paul Brown shared his thoughts about Motley during the induction.

“I’ve always believed that Motley could have gone into the Hall of Fame solely as a linebacker if we had used him only at that position,” Brown said. “He was as good as our great ones (on defense, too).”

For the next few decades, Motley bounced around between various jobs including the postal services, the Ohio Lottery, and the Ohio Department of Youth Services.

He passed away of prostate cancer in 1999 at the age of 79.

Motley’s influence in pro football was recognized long after he left the game.

In 1964, Graham told the assembled audience at a luncheon at Canton that there was no comparison between Motley and Brown, who would later eclipse all of Motley’s team records.

“There is no comparison between Jim Brown and Marion Motley,” Graham said. “Motley was the greatest all-around fullback.”

Noted pro football writer Paul Zimmerman wrote in his book The Thinking Man’s Guide to Pro Football that he believed Motley was the best player in the history of the sport.

And, in 2019, Motley was selected as one of the 12 running backs for the NFL’s Top 100 of All-Time Team.

While he was painfully rebuffed as a professional coach later in life, during his career Motley was recognized as a talented mix of imposing size, quickness, and agility.

To those who matter most, he will be remembered as a mighty trailblazer who paved the way for generations of African-American athletes that followed.

NEXT: How The "The Dawg Pound" Was Formed In Cleveland