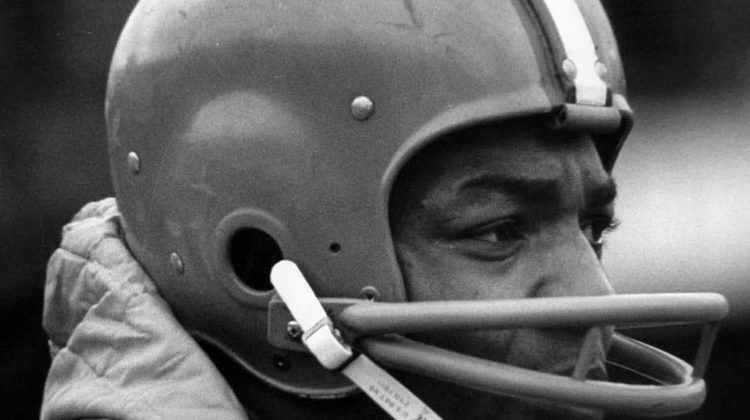

It was a matchup that appeared one-sided – future Pro Football Hall of Fame Baltimore Colts wide receiver Raymond Berry being covered by Cleveland Browns defensive back Walter Beach in the 1964 NFL championship game.

While Berry was strongly predicted to win the matchup, in fact, Beach generally outplayed Berry in the game, helping Cleveland shut out Baltimore 27-0 to win the 1964 NFL championship.

Beach played for Cleveland from 1963 to 1966, intercepting passes in consecutive NFL championship games in 1964 and 1965.

Honored to know Dr Walter Beach who played with Jim Brown & will be at Summit II as he was at the 1st Summit. #RMDP pic.twitter.com/po2cMpHeoO

— bobby glanton-smith (@GlantonSmith) September 8, 2015

We take a look at the life of Walter Beach – before, during, and after his NFL playing career.

The Early Years Before College

Walter Beach, III was born on January 31, 1933 in Pontiac, Michigan.

Pontiac is located about 20 miles northwest of Detroit.

In recalling his childhood, Beach said:

“Pontiac was Mississippi in the north. . . . Segregated, there was five movies. My father never went to the movie because he said he refused to go to a movie where he had to sit in the balcony, and sit in the back, and go up the back stairs, and pay for that. . . . As a kid, you know, I loved the movies. . . . I was the age where I’d pull for the cowboys and hope that the Indians fail. But that was before I became conscious. I didn’t recognize that I was an Indian. . . . [I]t was clear lines. In Pontiac, once you crossed Orchard Lake to come to the west side, you were in the white neighborhood. My junior high school, Washington Junior High School, was in a all white community. Of course, we had to go to that school but we could only go down one street. . . . So it was very segregated, so I grew up in that and I got all of my strength out of that from my grandmother, and my mother and father, and the community.”

Beach appreciates the upbringing he received from his parents.

“[Beach’s mother] said, ‘Wrong is right, and right is wrong. Wrong don’t right nobody, and right don’t wrong nobody.’ That was the message I got from my mother and father, so that’s kind of how I lived. . . . That kind of responsibility is kind of the way I live my life. That was an early lesson for me. I call them love lessons. I had a lot of love lessons.”

Beach attended Pontiac Central High School.

At Pontiac Central High School, Beach earned letters in football, basketball, and track.

Beach “held the state record in the 100 and 200 in track”.

He also played baseball for the American Legion.

After high school, Beach did not immediately attend college.

Instead, Beach went into the U.S. Air Force.

Beach spent four years in the U.S. Air Force (three years in Germany) as a cryptographic operator, enciphering and deciphering messages.

When Beach returned from his stint in the U.S. Air Force, such colleges as Michigan and Michigan State recruited him.

However, after Beach’s mother was impressed with Central Michigan College football head coach Bill Kelly on a recruiting visit, Beach decided to attend Central Michigan College in Mount Pleasant, Michigan.

College Years

Beach lettered in football at Central Michigan from 1956 to 1959.

He was the only African-American player on the team.

While Beach was there, Central Michigan competed in the Interstate Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (“IIAC”), with Illinois State, Eastern Illinois, Southern Illinois, Western Illinois, Northern Illinois, and Eastern Michigan.

With an unbeaten 9-0 record, Central Michigan won the IIAC championship in 1956.

As a sophomore, in 1957, Beach began to star as a back for Central Michigan.

In 1957, Beach led Central Michigan in rushing with 1,084 yards on 140 attempts (7.7 average yards per rushing attempt).

He also led Central Michigan in receiving with 27 pass receptions for 313 yards.

For his play in 1957, Beach was named first-team All-IIAC.

Central Michigan posted a 4-6 record in 1957.

Beach, in 1958, again led Central Michigan in rushing with 929 yards in 129 attempts (7.2 average yards per rushing attempt).

He also again led Central Michigan in receiving with 16 pass receptions for 264 yards.

In each of games in 1958 against Hillsdale, a 19-13 Central Michigan win on September 27, 1958 (including a 61-yard touchdown run by Beach), Illinois State, a 33-6 Central Michigan victory on October 4, 1958, Northern Illinois, a 33-23 Central Michigan triumph on October 18, 1958 (including a 68-yard touchdown run by Beach), and Eastern Illinois, a 27-8 Central Michigan win on November 1, 1958 (including a 74-yard touchdown run by Beach), Beach scored two touchdowns.

For his play in 1958, Beach was named a first-team “Williamson” All-American, Most Valuable Player in the IIAC, and first-team All-IIAC.

He also won the Herb Deromedi Most Valuable Player award at Central Michigan.

In 1958, Central Michigan had a 7-3 record.

Beach again won the Herb Deromedi Most Valuable Player award at Central Michigan in 1959.

Central Michigan, in 1959, again had a 7-3 record.

Over his four seasons at Central Michigan, Beach rushed for 2,968 yards and caught 62 passes for 928 yards.

While at Central Michigan, Beach also ran track.

He ran a school record-tying time of 9.7 in the 100-yard dash.

After his final season at Central Michigan, Beach played in the College All-Star Game in 1960.

Beach graduated from Central Michigan with a bachelor’s degree in sociology in 1960.

The Pro Football Years

1960-1963

Beach was drafted by the New York Giants in the 15th round of the 1960 NFL draft.

He was the 180th overall pick.

However, the Giants released Beach in training camp.

Beach then signed with the Boston Patriots in the American Football League (“AFL”).

In 1960, Beach played in six, and started two, regular-season games for Boston.

On September 23, 1960, Beach caught two passes for 50 yards, in a 13-0 Patriots loss to the Buffalo Bills.

Beach also returned one kickoff for 24 yards and one punt for 21 yards.

In a 45-16 Boston loss to the Los Angeles Chargers on October 28, 1960, Beach scored his first professional football regular season touchdown on a 51-yard pass from Boston quarterback Butch Songin.

Beach caught six passes for 80 yards and returned four kickoffs for 65 yards.

For the 1960 season, Beach caught nine passes for 132 yards and the above-described one touchdown and returned seven kickoffs for 146 yards and the above-described one punt for 21 yards.

Boston finished in fourth place in the AFL East division in 1960, with a 5-9 record.

In 1961, Beach moved to the defense.

He played in 12, and started 10, regular-season games at right cornerback for Boston.

On September 9, 1961, Beach had his first professional football regular season interception, when he intercepted New York Titans quarterback Al Dorow and returned the interception for 37 yards, in a 21-20 Patriots loss to the Titans.

Beach, for the 1961 season, had the above-described one interception, which he returned for 37 yards, and returned two kickoffs for 38 yards.

With Beach at right cornerback, the Patriots defense in the 1961 AFL regular season ranked third in fewest points allowed (313), third in fewest total passing and rushing yards allowed (4,123), second in defensive recovered fumbles (20), first in sacks (44), first in fewest rushing yards allowed (1,041), and first in lowest average yards per rushing attempt allowed (3.0).

Boston, with a 9-4-1 record, finished in second place in the AFL East division in 1961.

Beach expected to return to the Patriots in 1962, but an off-the-field incident caused Beach to leave the Patriots and ultimately join the Cleveland Browns.

“[W]e were going to New Orleans. . . . This was an exhibition game. When I saw the itinerary, it had all of the black ball players staying in one place and all of the white ball players staying in another place when we were going to New Orleans, I wasn’t comfortable with that. . . . So I talked to some of the players and they said, ‘Yeah, we should go talk to management about that.’ I was the spokesman for the group, so I said this is the way we feel about going to stay in a segregated quarters. . . . My position was, ‘Why don’t you just fly us in, let us play, and fly us out? Why do we got to go down there and stay two or three days?’ . . . When I spoke on that, and I shared that with management and everything, because I was the spokesman. The very next day I was on waivers. They sent me home. Gave me a check and told ne to go home.”

In 1962, Beach did not play in the NFL.

Instead, he worked as an elementary school teacher in his hometown of Pontiac, Michigan.

While working as a teacher, Beach’s friend, Cleveland Browns defensive back Jim Shorter, told Beach to contact Cleveland about playing for the Browns.

Beach contacted the Browns, and Cleveland sent Beach a contract.

Playing at a height of six feet and a weight of 190 pounds, Beach saw very limited action for the Browns in 1963, playing in only one regular-season game.

Cleveland, with a 10-4 record, finished in second place in the NFL East division in 1963.

1964-1966

1964 turned out to be Beach’s best NFL season, but it almost ended in training camp.

The Browns were planning to release Beach in training camp until future Pro Football Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown intervened.

Brown urged Cleveland not to release Beach, as Brown argued that Beach was a quality player.

The team listened to Brown.

Beach not only made Cleveland’s roster in 1964, but he also was the team’s starter at right cornerback for all 14 regular-season games.

1964 Cleveland @Browns Players. Source: @Cleveland_PL Sports Research Ctr. 1964 Championship Program. pic.twitter.com/lBbUsOStoX

— John Skrtic (@SkrticX) March 18, 2021

Beach helped the Browns allow only one offensive touchdown, in a 27-13 Cleveland victory over the Washington Redskins on September 13, 1964.

On September 27, 1964, Beach intercepted Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Norm Snead and returned the interception for 16 yards, as the Browns defeated the Eagles 28-20.

With Beach at right cornerback, Cleveland allowed only one offensive touchdown, in a 27-6 Browns win over the Dallas Cowboys on October 4, 1964.

Beach’s play contributed to Cleveland forcing five Dallas turnovers and having three sacks in another Browns victory over the Cowboys, 20-16 on October 18, 1964.

The following week, on October 25, 1964, with Beach at right cornerback, Cleveland forced six New York turnovers and had two sacks, as the Browns defeated the New York Giants 42-20.

In the next game, on November 1, 1964, Beach helped the Browns hold the Pittsburgh Steelers to only 86 “net” passing yards, in a 30-17 Cleveland victory over the Steelers.

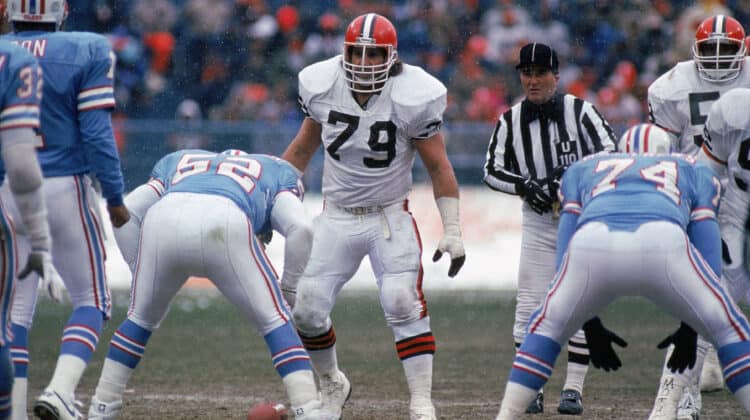

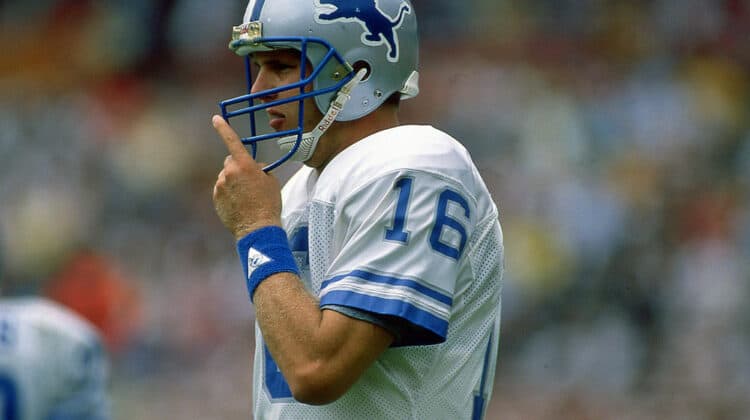

On November 15, 1964, Beach had two interceptions of Detroit Lions quarterbacks Milt Plum and Sonny Gibbs – one that he returned for a 65-yard touchdown (for his only NFL regular season touchdown).

The Browns defeated Detroit 37-21.

Beach had another interception, in a 38-24 Cleveland win over the Philadelphia Eagles on November 29, 1964.

On December 12, 1964, in a 52-20 Browns victory over the New York Giants, Beach’s play helped Cleveland force four Giants turnovers and have four sacks.

In 1964, Beach had the above-described four interceptions, which he returned for a total of 81 yards.

He also recovered one fumble.

Beach helped the Browns defense in the 1964 NFL regular season rank fifth in fewest points allowed (293), fourth in defensive forced turnovers (40), tied for second in defensive recovered fumbles (21), and tied for fifth in defensive interceptions (19).

Cleveland, with a 10-3-1 record, won the NFL East Division title in 1964.

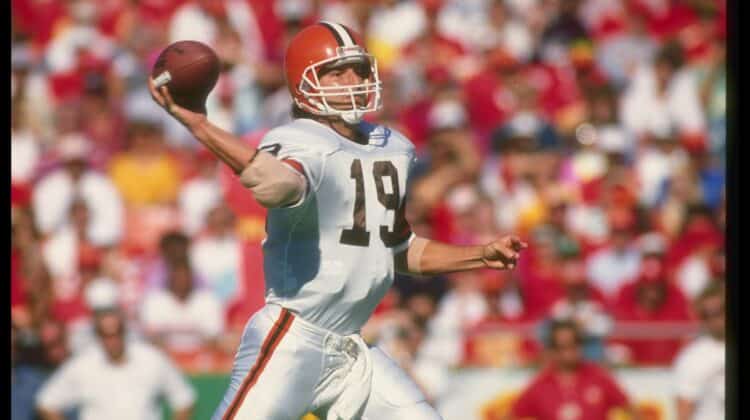

The Browns next played the Baltimore Colts in the 1964 NFL championship game on December 27, 1964.

The Colts were strongly favored to defeat the Browns, in part because of the matchup between Colts wide receiver Raymond Berry and Beach.

“Raymond Berry was the man . . . the toughest receiver in the NFL. That’s another reason why we were underdogs. People figured he’d catch everything, but I shut him down.”

Cleveland’s defensive gameplan was to play close, and not give any cushion, to Baltimore’s wide receivers, including the future Pro Football Hall of Famer Berry.

“A couple of times in the game, I looked into the eyes of [future Pro Football Hall of Fame Baltimore quarterback] Johnny Unitas. . . . If it was third and 12, when I’d crowd Raymond Berry, and I’d look up and I’d see Johnny Unitas kind of made a decision that I was too close and he’d have to look somewhere else.”

Covering Berry for most of the game, Beach (who started the game) held Berry to only three pass receptions for 38 yards.

Beach also intercepted a Johnny Unitas pass in the fourth quarter and returned the interception for nine yards.

Beach’s play helped Cleveland shut out Baltimore 27-0.

The Browns defense held the Colts (who had led the NFL regular season in 1964 in both points scored and total passing and rushing yards) to only 181 total yards (including 89 “net” passing yards and 92 rushing yards), forced four turnovers, and had two sacks.

For Beach, winning the 1964 NFL championship was a special moment.

“[W]inning the Championship was just one of those forever moments. I mean, I was euphoric. When I walked off the field, I felt I was walking on air. I remember it. I was so excited and so happy. . . . Nobody thought we would win . . . Nobody but us.”

In 1965, Beach played in 10, and started six, regular-season games at right cornerback.

Beach was part of a Cleveland defense that held opposing offenses to less than 300 total yards in six regular season games in 1965 – 232 total yards (including only 24 rushing yards), in a 17-7 Browns defeat of the Washington Redskins on September 19, 1965 (Cleveland forced one Washington turnover and had one sack), 252 total yards (including only 77 “net” passing yards), in a 24-19 Browns victory over the Pittsburgh Steelers on October 9, 1965 (Cleveland forced three Pittsburgh turnovers and had two sacks), 264 total yards, in a 23-17 Browns win over the Dallas Cowboys on October 17, 1965 (Cleveland forced one Dallas turnover and had four sacks), 293 total yards, in another defeat of the Cowboys, 24-17 on November 21, 1965 (Cleveland forced three Dallas turnovers and had four sacks), 201 total yards, in a 24-16 Browns victory over the Washington Redskins on December 5, 1965 (Cleveland forced three Washington turnovers and had two sacks), and 160 total yards (including only 50 “net” passing yards), in a 27-24 Cleveland win over the St. Louis Cardinals on December 19, 1965 (Cleveland forced four St. Louis turnovers and had two sacks).

In the 1965 NFL regular season, Beach contributed to the Cleveland defense ranking fifth in defensive interceptions (24).

With an 11-3 record, the Browns in 1965 again won the NFL East Division title.

Cleveland advanced to the NFL championship game for the second consecutive year, playing the Green Bay Packers in the 1965 NFL championship game on January 2, 1966.

For the second consecutive year, Beach (who started the game) had an interception in the championship game, when he intercepted future Pro Football Hall of Fame Packers quarterback Bart Starr.

However, the Browns lost to the Packers 23-12.

Beach played in five, and started four, regular-season games in 1966 at right cornerback.

On September 11, 1966, Beach intercepted future Pro Football Hall of Fame Washington quarterback Sonny Jurgensen, as Cleveland defeated the Washington Redskins 38-14.

Beach’s interception was one of six Washington turnovers that Cleveland forced in the win over Washington (the Browns also had three sacks).

In 1966, Beach was part of a Cleveland defense that forced at least four turnovers in seven other regular season games in addition to the Washington game – five turnovers by the St. Louis Cardinals, in a 34-28 Browns loss to the Cardinals on September 25, 1966 (Cleveland also had one sack), six turnovers by the New York Giants, in a 28-7 Browns victory over the Giants on October 2, 1966 (Cleveland also had three sacks), six turnovers by the Pittsburgh Steelers, in a 41-10 Browns win over the Steelers on October 8, 1966 (Cleveland also had two sacks), four turnovers by the Dallas Cowboys, in a 30-21 Browns defeat of the Cowboys on October 23, 1966 (Cleveland also had five sacks), four turnovers by the Philadelphia Eagles, in a 27-7 Browns victory over the Eagles on November 13, 1966 (Cleveland also had three sacks), four turnovers by the Washington Redskins, in a 14-3 Browns win over Washington on November 20, 1966 (Cleveland also had three sacks), and five turnovers by the Philadelphia Eagles, in a 33-21 Browns loss to the Eagles on December 11, 1966 (Cleveland also had one sack).

In addition to the above-described one interception, in 1966, Beach recovered one fumble.

Beach contributed to the Browns defense in the 1966 NFL regular season ranking fifth in fewest points allowed (259), first in defensive forced turnovers (49), fourth in defensive recovered fumbles (19), and first in defensive interceptions (30).

Cleveland, with a 9-5 record, finished tied for second place in the NFL East division in 1966.

1966 was Beach’s final season in the NFL.

The Years After The NFL

Beach married Gail.

In 1967, Beach attracted national attention when he was part of a group of African-American athletes (including Jim Brown, Jim Shorter, and other former Cleveland Browns players, including Bobby Mitchell, Sid Williams, Willie Davis, and John Wooten) who publicly supported the decision of boxer Muhammad Ali to refuse to be drafted in the U.S. military.

The Muhammad Ali Summit, 53 years ago today.

Front Row: Bill Russell, Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Standing: Carl Stokes, Walter Beach, Bobby Mitchell, Sid Williams, Curtis McClinton, Willie Davis, Jim Shorter, and John Wooten. pic.twitter.com/BAkZHVKmv4

— Andrew Ramsammy (@ramsammy) June 4, 2020

“We were men coming together around a moral and ethical issue. No one paid us any money to travel from all over the country to come together in Cleveland and basically put our careers in jeopardy by taking a controversial stand. We just did it.”

Throughout his life, Beach has spoken out against racism and on related issues.

“This is a message for the young men and young ladies in this room. If you don’t understand racism and how it works, everything else will confuse you. You need to know how to get busy. Not with your fists, but with your minds and talents.”

After his playing days in the NFL, Beach was involved in various activities, including that he owned Beach Investment and was CEO of Amer-I-Can (a life skills management program that was founded by Jim Brown), Special Assistant to the Mayor of Cleveland, Carl Stokes, a training director of the New York City Department of Corrections, a trainer of child welfare counselors for the City of New York, and an assistant principal of an elementary school in New York City.

Beach attended Yale Law School.

In 2014, Beach wrote a memoir, Consider This.

He settled in Pennsylvania.

Beach was inducted into the CMU Hall of Fame in 1985.

Browns fans should appreciate Beach’s outspoken nature, as it resulted in him leaving the Patriots and joining the Browns in 1963.

In assessing Beach’s career, it is important to remember that he did not first play professional football until he was 27 years old (in 1960) because of the four years he served in the U.S. Air Force.

In addition, it should be noted that Beach missed an entire season in 1962 (and barely played in 1963) after he was released by the Patriots.

Beach did not play in many games for the Browns (only 32 regular season and playoff games), but he was part of a great period of Cleveland football.

During his four years from 1963 to 1966, the Browns compiled an aggregate regular-season record of 40-15-1 and advanced to two NFL championship games.

In those two NFL championship games in 1964 and 1965, Beach had an interception in each game.

Not too many NFL defensive backs can claim that they intercepted a pass in every playoff game in which they played (even more impressively, interceptions of two Pro Football Hall of Famers – Johnny Unitas and Bart Starr).

Beach’s play in the 1964 NFL championship game against Raymond Berry teaches the important lesson that expectations and predictions do not win championships; instead, it is actual performance that wins a championship.

Notwithstanding their respective “pre-game credentials”, Walter Beach generally outplayed Raymond Berry in the 1964 NFL championship game and helped Cleveland shut out the Colts and earn its last NFL championship.

NEXT: The Life And Career Of Dick Modzelewski (Complete Story)