The colossus that is today’s NFL consists of players from many walks of life.

The stars of the game hail from every nook and cranny of the country as well as various foreign countries.

This was not always the case, however.

For a period of time, the NFL mirrored the other major North American pro sports leagues in shutting out athletes of color.

Specifically, from the early 1930s until 1945, no NFL team employed African-Americans.

Thankfully, this changed in 1946 when the Los Angeles Rams and Cleveland Browns signed the first modern day African-American athletes to contracts.

The Rams signed Woody Strode and Kenny Washington.

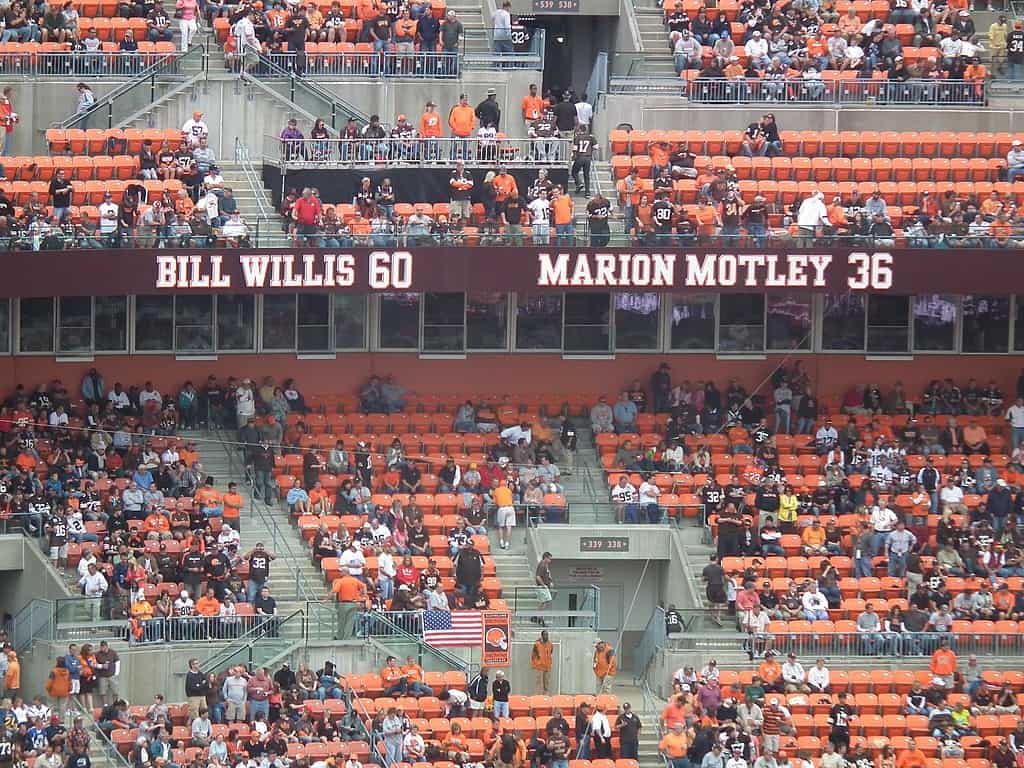

The Browns inked defensive lineman Bill Willis and running back Marion Motley.

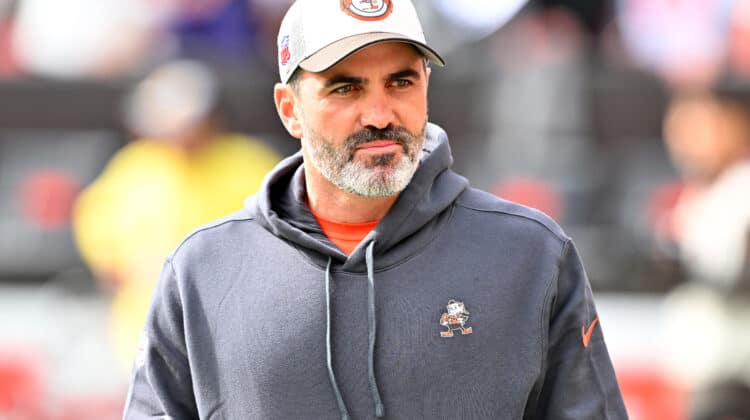

When the Browns were formed in 1944, head coach Paul Brown got to work signing a number of players who previously played for or against him.

Willis and Motley were two such players.

Willis came from Ohio State where Brown coached him in 1942 and 1943.

Motley played for Brown at the Great Lakes Naval Academy in 1944 and 1945.

Motley also played against Brown in high school where he attended Canton McKinley High School (Brown then coached at Massillon High School).

Both players’ rookie contracts were recognized as the top Artifacts of Inspiration by the Pro Football Hall of Fame last year.

Topping our list of the most inspirational artifacts are Marion Motley’s and Bill Willis’ 1946 rookie player contracts. Their success blew open the doors for many more African American players.

More: https://t.co/KDIJpjHgWU pic.twitter.com/vGAs1BMwaF

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) April 22, 2020

Willis Convinces Brown to Sign Him

It was almost an accident that Willis signed with Cleveland.

Having taken a job coaching at Kentucky State College in 1945, Willis read that Brown was forming a new team in the All-American Football Conference.

He gave his old coach a call and Willis was invited to a team tryout.

Brown challenged Willis by lining him up against center Mo Scarry.

It was quickly evident that Scarry was in over his head as Willis’ quickness dumfounded Scarry on every snap.

“He [Willis] was quick,” said Alex Agase, who later joined the Browns as a guard. “I don’t think there was anybody as quick at that position, or any position for that matter. He came off that ball with that ball as quick as anything you would want to see.”

https://twitter.com/KevG163/status/1313099352286670850

Brown was impressed and signed Willis, 10 days before he signed Motley.

Willis played in Cleveland from 1946-1953.

He was an NFL champion in 1950, a three time Pro Bowler, four time First-team All-Pro, four time AAFC champion, and a three time First-team All-AAFC.

Willis was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1977.

Motley Proves he Belongs

Much like Willis, Motley was about to move on with his life after serving in the military when he learned that Brown was putting together a Cleveland franchise for the new AAFC.

He contacted Brown and asked for a tryout.

However, Brown said no as he already had enough fullbacks.

Not long after, Brown changed his mind when he invited Willis to try out.

“I think they felt [Willis] needed a roommate,” Motley later said. “I don’t think they felt I’d make the team. I’m glad I was able to fool them.”

https://twitter.com/Ol_TimeFootball/status/1401340928531451905

Motley did make the team and Brown would be happy he reconsidered his original decision.

Over the course of his career, Motley rushed for 4,720 yards and averaged 5.7 yards per carry.

He was a four time AAFC champion, won the 1950 NFL Championship, led the AAFC in rushing in 1948 and led the league in rushing touchdowns a year later, was the 1950 NFL rushing leader, voted to the Pro Bowl in ’50, was a two time First-team All-Pro, and was voted to the NFL’s 1940s All-Decade Team, 75th Anniversary All-Time Team, and 100th Anniversary All-Time Team.

Motley was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1968.

Duo Honored by Hall

In April of 2020 the Pro Football Hall of Fame released its Top Ten Artifacts of Inspiration.

At number one, the Hall selected the rookie contracts of Willis and Motley.

The contracts were chosen as the best representations for stories of inspiration.

Both Willis and Motley (along with Strode and Washington) had to overcome overt racism not only away from the game, but during games as well.

Motley commented on what he and Willis experienced during plays, noting that the referees did nothing to help.

“Sometimes I wanted to just kill some of those guys, and the officials would just stand right there,” Motley said many years later. “They’d see those guys stepping on us and heard them saying things and just turn their backs. That kind of crap went on for two or three years until they found out what kind of players we were.”

It was because Willis and Motley overcame this racism to become trial blazers for other African-Americans that the Hall of Fame honored the duo.

NEXT: Observations From Cleveland Browns OTA's“The image of Strode, Washington, Motley and Willis on the field gave hope to millions of African Americans that they could live the American dream,” the Hall story commented. “The walls of segregation began to crack, and the Civil Rights movement gained steam. Willis’ and Motley’s dominance made professional football evaluators look foolish and lessoned the prejudice of their teammates and fans. Their success blew open the doors for many more African Americans players.”